What is Cognitive Parallax and How to Identify It

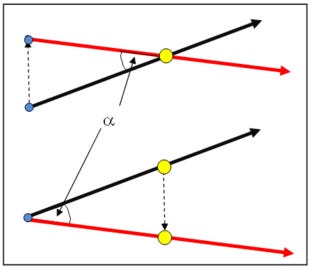

One of the most interesting concepts studied is, without a doubt, that of cognitive parallax. It is defined as “the distance between the axis of theoretical construction and the axis of real experience announced by the individual”, which would have expanded after Modernity. Previously, ancient and medieval philosophers (mostly) believed that they were within a rationally ordered reality or cosmos, without being able to observe it from the outside or modify it, at the base, according to their wishes or worldviews. Parallax is, in the definition, like a distortion of perception that ends up destroying the ability to reconcile factual truth and reflective theory, often even intentionally, as in Marx and Epicurus.

In debates, the concept of cognitive parallax demonstrates the contradiction between two principles or between the principle and the action that the individual announces. It is like following the following model:

(1) Do not enter;

(2) Entry here;

(2) is the direct negation of (1). And yet, the subject shouts everywhere the two ideas at the same time.

Some other examples, in humanist thought in general:

(1) The action of individuals is explained by current ideological and social influences within a system of historical materialism based on class conflict;

(2) Stalin’s crimes cannot be charged against his leftist ideology, as they were caused solely by the innate evil of this man;

Or yet:

(1) Knowledge is only valid if obtained by the scientific (or empirical) method;

(2) The knowledge obtained in (1) is valid, even if it is not obtained by the scientific method;

(1) There is no absolute truth;

(2) The above sentence, to be true, cannot contain exceptions;

(3) Therefore, the phrase (1) is an absolute truth, which, according to (1), does not exist;

And so it goes.

To identify a case of cognitive parallax, keep in mind if the opponent’s claim does not contradict the theoretical principles that he carries, in general, or that support the specific sentence itself. Conferring if the enunciated idea is sustainable in itself by the values of the other debater itself is an ex concessis refutation, as defined by Schopenhauer in the book Eristic Dialectic and, if the argument intends to be philosophical, it is even more lawful to demand that it be consistent with the general framework of the ideas of the interlocutor.